Content Warning: Due to the sensitive nature of these materials, as well as copyright issues, we have chosen to share only 3 or 4 images per text.

The industrious Black Mumbo serves as one of the most iconic characters of Helen Bannerman’s Little Black Sambo and its many adaptations. Frequently depicted sewing clothing for her son and, of course, cooking hundreds of pancakes, Black Mumbo represents cheerful domesticity and maternal bliss. Throughout the decades, her body has also functioned as a site on which illustrators have projected shifting cultural anxieties surrounding people of color, particularly women of color. Many later adaptations have also changed her name as creators increasingly recognized the negative connotations of “Black Mumbo” and, in some cases, strove to return the characters to their alleged Indian roots. This exhibit traces the visual evolution of Black Mumbo in order to highlight how changing cultural attitudes toward racial difference in America have influenced how illustrators portray Sambo’s mother.

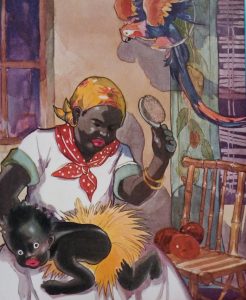

Bannerman’s original text and many early American adaptations negatively represent Black Mumbo as a racialized “Mammy” figure. In Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory, Kimberly Wallace-Sanders notes that the Mammy caricature derives from antebellum fiction and the slave plantation. Typically portrayed as an obese, black-skinned, middle-aged woman who wears an apron and a headscarf, the Mammy is a “jolly presence” that was used to justify slavery (6). Though Bannerman was a Scottish woman residing in India who had never traveled to America, her rendering of Black Mumbo nevertheless has echoes of the American Mammy caricature. The original Black Mumbo has a portly figure adorned with a headscarf. She wears no shoes, emphasizing her primitivity, and Bannerman draws her either holding a pot or eating at the table with her family, highlighting her domestic role. Other Americanized adaptations make Black Mumbo’s “Mammification” even more apparent. For instance, John R. Neill’s 1908 Little Black Sambo represents Black Mumbo as an obese woman with a bandana, an apron, and exaggerated red lips. Johnny Gruelle’s 1917 book All About Little Black Sambo also reinforces Black Mumbo’s status as a caricatured Mammy. Here, she appears with jet black skin, obscenely large lips that render her face more chimp-like than human, and the expected bandana and apron. Even versions that provide a more humane representation of the characters, such as Eulalie’s 1933 Nursery Tales Children Love, continue to depict Black Mumbo in stereotypical Mammy attire.

As the twentieth century progressed, illustrators increasingly chose to portray Black Mumbo as Indian rather than black, but many of these representations also remain deeply problematic. In 1930, Eunice Stephenson’s The Little Black Sambo Storybook refers to Black Mumbo only as “mother.” While this label avoids the troubling racial connotations of the original name, it also erases her individuality, reducing her merely to her maternal role. Stephenson also draws the woman wearing a stereotypical Orientalized headscarf and no shoes, features that would come to define the Indian versions of the character. Later, the 1971 adaptation Rama and the Tigers: A Tale of India changes Black Mumbo to the male name Lakshmana, a mistake that suggests that the creators were more concerned with using a name that sounds exotic and Orientalized than a culturally accurate name. Similarly, a 1983 reprint of Eulalie’s adaptation retains many of the illustrator’s original images, but it changes Black Mumbo’s name to Mama Sari and depicts her as a much slimmer Indian woman with her hair pulled back in a bun. Finally, Fred Marcellino’s 1996 adaptation The Story of Little Babaji also Orientalizes Black Mumbo, renaming her Mamaji–a name that, Sanjay Sircar notes, actually denotes a maternal uncle in most Indian languages rather than a mother figure–and drawing her with her hair in two buns, a primarily European style (204). Together, these radically divergent representations of Black Mumbo–as grotesque Mammy figure or as Orientalized mother–reveal America’s ever-shifting, unsettled approach to race and the Other.

View items in the Black Mumbo collection:

- Little Black Sambo

- Little Black Sambo in Stories Children Like

- A New Story of Little Black Sambo

- Little Black Sambo

- All About Little Black Sambo

- Little Black Sambo

- Little Black Sambo

- The “Pop-Up” Little Black Sambo (with “Pop-Up” Picture)

- The Story of Little Black Sambo

- Little Black Sambo

Credits

Brianna Anderson